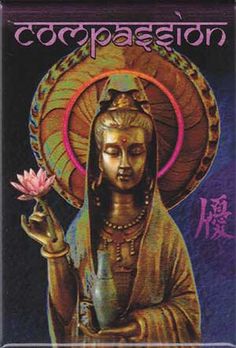

How Do We Practice Compassion in a World of Terrorism?

This question goes to the heart of the Buddha’s teaching. Over 2,600 years ago when the Buddha had his “Awakening” he came away with several epiphanies that would revolutionize his own life and bring practical wisdom to the difficulties and troubles of that world. One of the most significant of these is that there is suffering in the world, which he named a truth of existence. He said t this is both personal and universal and that it manifests in illness, injury, aging, death, warfare, and impermanence. We call this the First Noble Truth.

When this truth is accepted we come to understand that today’s terrorism is another form injury, warfare and death. It is usually unexpected, happens outside the rule of law, harms innocent people, and is seemingly uncontrollable. So when we comprehend that terrorism has always been present in some form it can relieve some of the shock and fear that arise around it. This in turn can lead to greater ease and less reactive behavior, which only spins the cycle of continued terrorist activity.

When this truth is accepted we come to understand that today’s terrorism is another form injury, warfare and death. It is usually unexpected, happens outside the rule of law, harms innocent people, and is seemingly uncontrollable. So when we comprehend that terrorism has always been present in some form it can relieve some of the shock and fear that arise around it. This in turn can lead to greater ease and less reactive behavior, which only spins the cycle of continued terrorist activity.

Yet, is this enough to open the doorway to compassion? Not completely. It is said in the Buddhist teachings “… that the proximate cause of the arising of compassion is suffering”. How is this true? Does it mean we have to suffer to be compassionate? What these words and the wisdom behind them points to is that when we experience suffering in any way a deep instinctual empathy arises for another or our self. The pain of the experience naturally opens our heart and ‘we feel with’; opened by this stark reality. It is a deep human response and makes us feel ‘one’ with another; connected and caring. This is the antidote to hatred; the gateway to peace.

In an article by Cheri Maples, a former policewoman, and practitioner of Thich Nhat Hanh we find these radical words of direction in the Buddhist spirit:

“The most frequent question I got asked as a Buddhist cop was, “How can you do this kind of work?”

It was Thay who put this question to rest for me. First, he asked me, “Who else would we want to carry a gun besides somebody who will do it mindfully?” Then he said that carrying a gun can be an act of love if done with understanding and compassion.

Once I was able to view my work through the lens of kindness and compassion, I rarely regretted any action that I took. I am convinced that when a police officer starts with a commitment to non-aggression and preventing harm, the gun and badge become symbols of skillful means, rather than symbols of authority and power.”

We can say the answer is in the issue itself, or that the remedy is through the pain. If we face contemporary world struggles, not back away from being present to it, our sorrow and anger may transform into compassion and understanding. Our conscience and our moral compass can give rise to an attitude of ‘non-harming’. And we then become the cure for the conflict not the cause of the crime.